One thing I can’t deny, the last three hundred years or so of history of the west has been a progression towards informality. Sure, there have been bumps on the road, but there is no mistaking, we’ve gone from a more formal culture to a less formal culture. One area that this is readily apparent is in dinner service.

As always, I’m going to be describing middle and upperclass service.

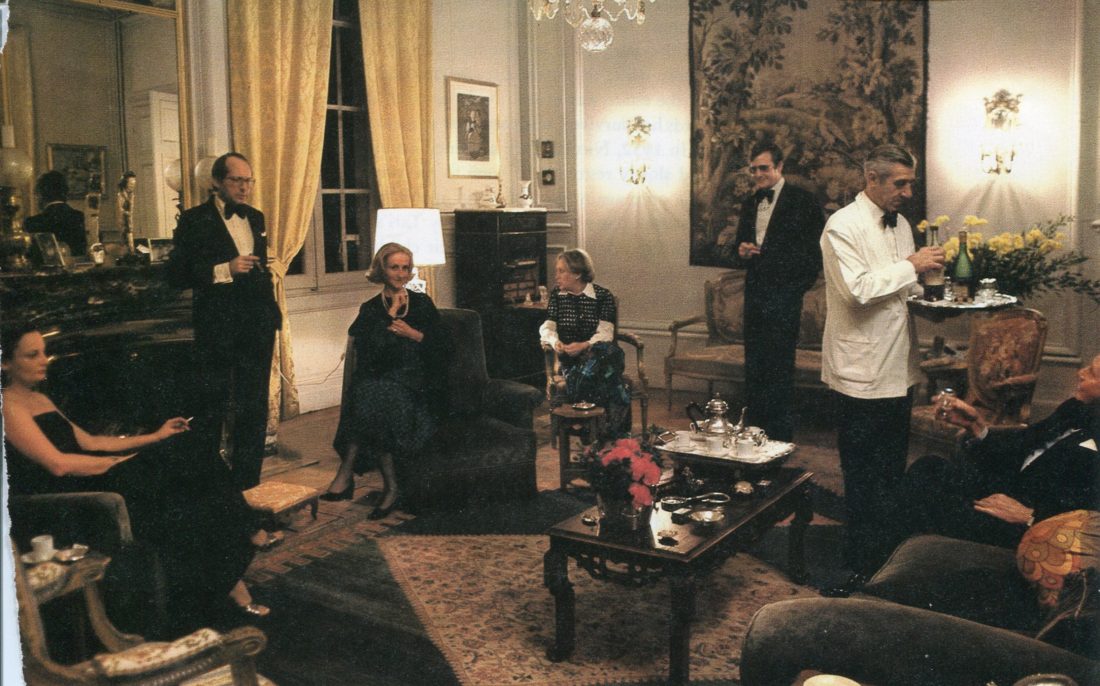

I want you to empty your mind of what you think informal service might include because to the Victorians through the Edwardians, informal dinner could include multiple courses, a butler pouring the wines and dressing in black tie for dinner.

Even into the fifties and sixties an informal dinner in some circles is what we would today mistakenly called a formal dinner. So what comprised an informal dinner?

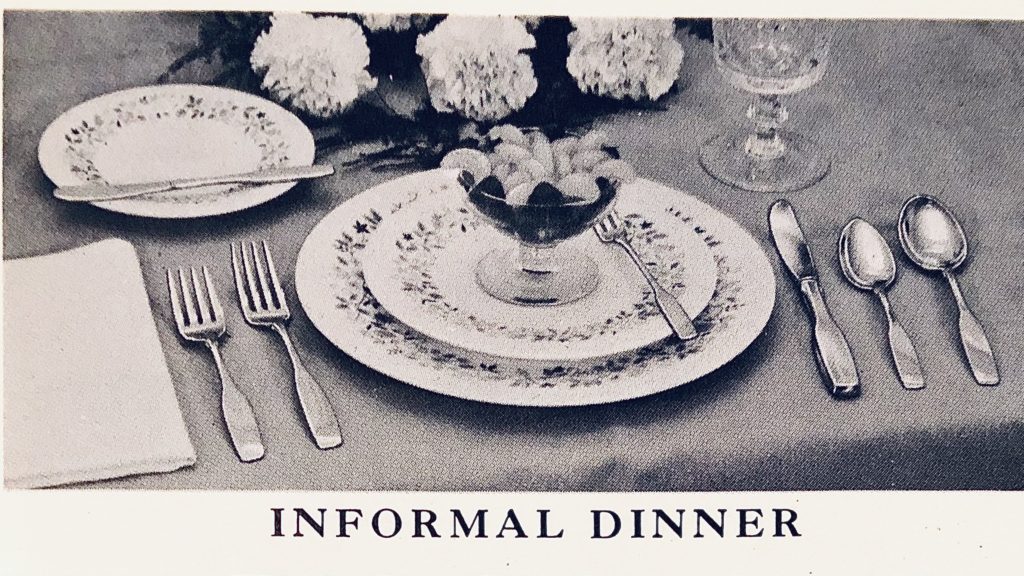

Firstly, as you can see above an informal dinner has a bread and butter plate, a formal dinner will never have one of these. That alone should tell you how formal an informal meal could be. Many people will have seen sterling silver bread and butter plates… sterling silver… they are not formal. Indeed, many houses repurposed sterling bread and butter plates to go under finger bowls or sorbet coups at formal affairs. I say this to point out that past informal meals might be seriously luxe.

An informal meal could be mastered with only a cook and one servant, (a waitress or a butler) though ideally one would have a cook, a butler and a waitress. The informal meal would likely be served Compromise Style, (refer to my earlier blog post on these) as this allowed for the lack of servants. The butler would stand behind the man of the house or in front of the sideboard so that he could watch the table and pour the wines. The waitress, (or footman) would bring the dishes into the dining room from the kitchen. If there was only one server, the host would be in charge of keeping his guests wine glasses filled.

If you want to know how the service for a late 19th century to early 20th century informal dinner would go, here is an approximation. Obviously, regional areas served different courses in different places:

After an aperitif or punch in the parlor, the guest would enter the dining room.

Often the first course would be already laid on the table as the guests walked into the room. Fruit cocktail, oysters or seafood cocktail were the norm, but any fancy appetizer that could be served cold or room temperature would do. Champagne was often served, though sometimes a muscadet was served instead.

Next soup would be served, it could be brought in and taken round to each guest by the server or would be placed in front of the hostess, who would fill each bowl and either pass it down or hand to the servant who would take each bowl to its place. Sherry would be served with this course.

The next course would be a fish course. This would be brought in on a platter by the server, and each guest would take a portion. Hock, (a general term for a German white wine like a Riesling) wine would be served chilled. Though not as cold as we have our white wine today.

In a wealthy household, you.might now be served an entree. This would be game or poultry. A lighter red would be served.

Next the main course would be served. This was generally a large cut of meat, though beef Wellington would do. This was usually brought in and placed in front of the host to be carved at the table. The dinner plates would be brought in with the meat, the cook having warmed them so as not to shock the meat. Claret, (a red, usually Bordeaux wine) would be served.

In areas that were French influenced a salad course followed which came with only water.

After that dessert and/or cheese and fruit with ice cold champagne would be served. Port could also be obtained for those who wanted it.

At this point the ladies and gentlemen would split up. The ladies would withdraw to the parlor, (this is how the drawing room got its name). The men would now drink brandy and smoke cigars. Often, if smoking was not allowed in the dining room, which in many American homes it was not, the men retired to the games room or library. The ladies would be served demitasse coffee and sweet champagne. A dessert wine could be offered and there might be cookies or chocolates. In the 19th century the sexes might be split for a half hour or more, but by the twenties, this was reduced to fifteen or twenty minutes at the most.

Does this seem informal to you?

By the twenties informal dining had become shorter with five courses as the norm. Now an informal meal might have an appetizer, soup, fish, main and dessert or fruit and cheese. Some regions would have served an appetizer, soup, fish, main, salad and then had confectionary with coffee after the meal.

As I discussed in my post on the modern formal or company dinner, by the forties, formal dinners would have maxed out at five courses and so the informal meal generally had four. Appetizer, soup, main course and dessert.

Even though the informal dinner became what we would recognize as the meal served at most banquets and weddings, do not mistake it for a company dinner. Rules of etiquette still held a tight grip on the informal dinner well until the nineteen nineties.

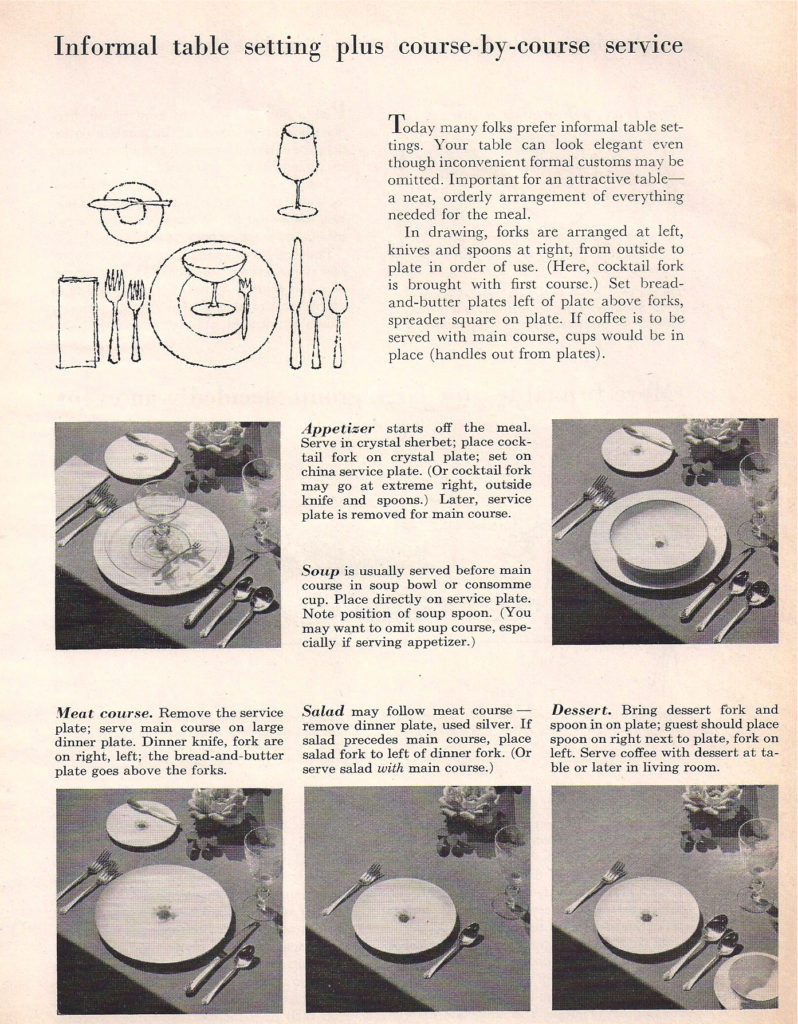

As you can see below, in the sixties the informal dinner still had five courses, but importantly, times they were a changin’ and the nice people at Better Homes and Gardens were already selling everyone to omit “inconvenient formal customs”. It was about this time that informal stopped universally meaning black tie. People went to an informal meal in business suits and fewer and fewer men owned a bespoke tux. Neck ties replaced black bow ties and ladies were allowed to wear cocktail length dresses.

Now I am loathe to be a snob, but what in the mid-western hell are they thinking saying it’s ok to serve coffee with the main course? That’s just a big old yuck. Don’t do it.

So, would you give a historic informal dinner a try? I don’t know if people would be willing to give up three or four hours to take a meal with someone at their house. Let me know what you think?

Sending you much warmth and love, Cheri